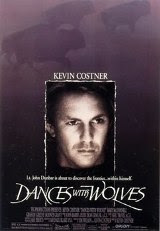

Filled with lush settings, costumes and cinematography, Kevin Costner’s directorial debut is an absolute eye-pleaser. Turning Western film conventions on their heads, Dances with Wolves’ subtleties and melancholy tones won over audiences and Oscar voters alike, making it one of the best and most successful anti-Westerns of all time.

Filled with lush settings, costumes and cinematography, Kevin Costner’s directorial debut is an absolute eye-pleaser. Turning Western film conventions on their heads, Dances with Wolves’ subtleties and melancholy tones won over audiences and Oscar voters alike, making it one of the best and most successful anti-Westerns of all time.I use the term anti-Western because the film defies most of the generalizations and stereotypes that had become the norm in “cowboy and Indian” flicks. Gone is the notion that the white man is good and virtuous in his move westward. Likewise, the archetypal angry Indian savage has been thrown out the window. This is not to say that the roles have been reversed, because they haven’t. Instead, Costner aims to depict both parties objectively, as genuine human beings with parallel virtues and flaws.

The South Dakota setting is the first step in the right direction. Instead of filming in the barren desolation of Monument Valley, Dances with Wolves tells its tale on the rugged prairies of the Great Plains. While you wouldn’t think that hill after hill would be much to look at, the vastness is quite gripping. For parts of the film, Costner’s only screen partners are the hills and the sky that eventually bends down to meet them. It is the essence of both wonder and vulnerability.

Costner plays Lt. John Dunbar, a man whose suicidal antics on the Civil War battlefield gets him labeled a hero and earns him a ticket to whatever outpost he likes. He chooses one of the most remote outposts on the western frontier. He finds it abandoned and in disarray. As the only tenant, he does his best to get the fort up to snuff. As he waits for the reinforcements that may never come, Dunbar has frequent visits by a curious wolf and tense encounters with the native Sioux Indian tribe.

Dunbar ultimately finds ways to ease the tension between himself and the Sioux and they form a mutual respect for each other. As his relationship with the Sioux builds, Dunbar finds himself more and more disenfranchised with the ways of the supposedly civilized white man and finds himself sympathetic to the Sioux cause. He finds friendship, dignity, love and inner peace with the natives and is forced to choose sides when US troops finally make their way to his fort, delivering harsh doses of Westward Expansion to anyone standing in their way.

The concept of “going native” was not new with this film but the process is head and shoulders above the rest because Costner allows plenty of time for Dunbar’s transformation to take place. At three hours long, Dances with Wolves is a sprawling tale. Without that kind of length, the story would have been shortchanged and Dunbar’s shift in allegiances would have seemed rushed.

While a three hour run time may have been necessary for the story to seem plausible, the film is not without its share of dull moments. The voice-overs and cinematography really help capture Dunbar’s isolation but there are times in the film when I felt more desperate for something to happen than Dunbar. It is very difficult for one person to be the focus of a film for a great length of time. Costner’s dry, matter-of-fact tone in the voice-overs doesn’t help much when you begin to feel less engaged by the film’s central character. A few years ago, Costner released a director’s cut version of the film that added an additional hour to the film’s run time. While the film is a real treat and a triumph at three hours, I fear that four hours would begin to try my patience.

This film makes sense as an Oscar winner for Best Picture. While many movie fans like to scoff and say that Goodfellas was more deserving, you have to understand how the Academy works. Dances with Wolves is sympathetic and empathetic with a downtrodden people. It helps to right some of the wrongs done to Native Americans over the years in cinema and television and challenges our notions of what is right, both historically and sociologically. Costner has crafted a thinking man’s Western that strives to be anything but a Western. That in and of itself makes Dances with Wolves a fantastic film to watch.

RATING: 3.75 out of 5